Core versus overall measures of inflation. As ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet explained:

Euro area annual HICP inflation was 2.6% in March 2011, according to Eurostat’s flash estimate, after 2.4 % in February. The increase in inflation rates in early 2011 largely reflects higher commodity prices. Pressure stemming from the sharp increases in energy and food prices is also discernible in the earlier stages of the production process. It is of paramount importance that the rise in HICP inflation does not lead to second-round effects in price and wage-setting behaviour and thereby give rise to broad-based inflationary pressures over the medium term. Inflation expectations must remain firmly anchored in line with the Governing Council’s aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.That is, the recent blip in inflation is largely due to energy prices, but the worry is that this will lead to higher wage demands and ultimately more general price increases. This would be particularly bad if people began to make plans based on expectations of higher inflation (i.e., expectations became un-"anchored"). Those worries are ill-founded, says Paul Krugman:

Overall eurozone numbers look very much like US numbers: a blip in headline inflation due to commodity prices, but low core inflation, and no sign of a wage-price spiral. So the same arguments for continuing easy money at the Fed apply to the ECB. And the ECB is not making sense: it’s raising rates even as its official acknowledge that the rise in headline inflation is likely to be temporary.Former Fed governor Larry Meyer had a nice op-ed on the subject in the Times last month.

Inflation targeting and "credibility." A temporary energy-price driven inflation spike may be harder for an inflation-targeting central bank like ECB to brush off. The goal of inflation targeting is to make monetary policy credible - i.e., to keep inflation expectations anchored - but it only works if the announced target is met. Gavyn Davies writes:

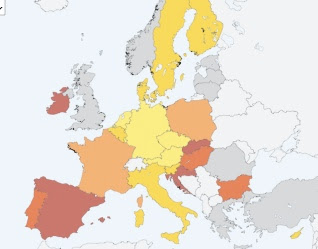

Of course, when an adverse supply shock hits the economy, there are no easy paths for the central bank to adopt, and the ECB will protest that its mandate requires it to hit its CPI inflation target regardless of the consequences for GDP growth. But it can expect no praise if it pushes the economy back into recession.The optimum currency area problem. Or, really, the problem that the euro zone isn't one. The single currency means a single monetary policy. That works if the economies of Europe move together, but they aren't. This map of unemployment rates across Europe illustrates the problem:

The lightest yellow shade are countries with unemployment rates below 7% and the darkest red have rates above 13%, including 14.9% in Ireland and 20.5% in Spain. (A small irony: Eurostat's nifty map tool makes it very easy to illustrate the fundamental flaw of the euro project). In the high unemployment countries, it is hard to imagine that workers would be in a strong position to demand higher wages to make up for the increase in energy prices. But Trichet's worry may make more sense in the parts of Europe where labor markets are tighter. And Trichet can only make one monetary policy. As Floyd Norris puts it:

“If you take the euro area as a whole . . .”This is exacerbated by the fact that several of the smaller eurozone countries are also undergoing sovereign debt crises. David Beckworth has the appropriate musical reference - it may be the final countdown for Europe:

So began a response Thursday from Jean-Claude Trichet, the president of the European Central Bank, as he explained the central bank’s decision to raise interest rates in Europe.

If only there were a “euro area as a whole.”

[T]his move may have begun the countdown to the Eurozone breakup. It is hard to see how else this can turn out. The Germans--the folks who really call the shots in Europe--are reluctant to see the needed debt restructuring in the periphery and are equally reluctant to provide bailouts large enough to fix the problem. So far the Germans have been kicking the can down the road on these issues. With ECB monetary policy now tightening they will soon run out of road to kick the can down.One irony here is that many of the same sorts of people who have taken to criticizing the Fed for "printing money" are also prone fretting that America is sliding down the slippery slope to "European socialism" (trains and universal healthcare - quelle horreur!). Next time Ron Paul says we need to return to "sound money", someone needs to tell him to move to Europe!

3 comments:

A few thoughts:

1) Core versus overall measures of inflation and inflation targeting "credibility." .

Headline inflation makes a very poor target. Eurozone yoy headline HICP has whipsawed all over the place in the last four years from a high of 3.5% in October 2008 to a low of 0.3% in March of 2010 to its current level. Meanwhile core has has been very well behaved, except that it has fallen a great deal, from 1.9% in early 2008 to 1.0% currently.

In fact if the ECB had been following core instead of headline they might have been loosening instead of tightening in the middle of 2008, and we all know where that got us.

It's hard to keep your credibility when you're targeting such a volatile target.

2) The optimum currency area problem.

Everything is relative. What is really an "optimum currency area"? Nothing. But is the Eurozone necessarily worse than the US (similar population and output). Absolutely not.

If one compares real GDP in 2009 versus trend growth from 1997-2007 one will find all the Eurozone-16 members were 6-10% below trend except Cyprus(5%), Finland(14%), Ireland (21%) Luxembourg(11%) and Malta (3%). Those nations account for little more than 3% of the eurozone’s output. The difference between Spain and Germany’s performance by this measure is trivial (10% versus 7%).

Do a similar comparison for the US and what you find is far greater dispersion in growth relative to trend. The following states were over 11% below trend: Arizona (16%), Florida (14%), Georgia (11%), Idaho (12%), Michigan (12%) , Nevada (18%), Oregon (11%). All told they account for roughly 15% of US GDP. The following states were less than 7% below trend: Alabama (7%), Alaska (-8%), Arkansas (4%), Colorado (6%), DC (3%), Hawaii (6%), Kansas (6%), Kentucky (5%), Louisiana (-2%), Maine (6%), Maryland (6%), Massachusetts (7%), Mississippi (3%), Montana (5%), Missouri (6%), Nebraska (5%), New Mexico (6%), North Dakota (-4%), Oklahoma (-8%), Pennsylvania (5%), South Dakota (0%), Vermont (6%), Virginia (7%), Washington (6%), West Virginia (-1%) and Wyoming (-12%). All told these states account for roughly 13% of US GDP.

So states accounting for 28% of US GDP were outside of the 7-11% below trend range versus countries accounting for 3% of Eurozone-16 GDP that were outside the 6-10% range. More substantial statistical analysis of the relative degree of dispersion involving weighting shows similar results.

Granted, there is greater labor mobility in the US, but this does raise the issue of which is really the better OCA, the US or the Eurozone. Despite the lack of awareness on this issue, there is actually a huge diversity in regional economic performance in the US.

It also underscores the fact that despite all of Germany’s bravado they are not vastly outperforming the rest of the Eurozone. Kurzarbeit obscures the fact that in Germany, real GDP, exports, manufacturing, productivity etc. are still lower now than they were three years ago. The ECB’s tight money policy is not only bad for the periphery it is bad for the core, and the proof lies in the fact that Iberia and Greece are not doing all that much worse than Germany and France, and the gap is far less than that between some large US states.

Thanks. I agree, headline inflation is problematic, but if the ECB has announced that's what they're focusing on, then they risk their credibility when they don't respond to it. More broadly, I think one could argue based on recent experience that if you want to have inflation targets, core measures are better, and the target level should be higher than 2%. But once you've set a target, changing it raises a credibility issue.

On the optimal currency area - that's a fair point about the US (and I actually meant to mention that..). I know there's some academic literature on whether the US is an optimum currency area, though the exact citation escapes me at the moment.

Post a Comment