The US economy grew at a 1.8% annual rate in the first quarter, according to the BEA's advance estimate. That's not good - it less than the 2.5%-ish pace needed to keep the unemployment rate stable as the labor force grows and productivity increases - and way short of what we need to significantly bring unemployment down.

The slow growth wasn't a surprise, and much the slowdown is being attributed it to temporary factors, including the severe weather in January, and a slowdown in defense purchases.

The main positive contributions came from consumption, which grew at a 2.7% rate, and inventory investment, which was something of a "bounceback" effect - the actual amount added to inventories was modest, but it was an acceleration relative to the fourth quarter, when there had been a big slowdown.

The government purchases component was a drag, falling at a 5.1% annual rate (defense fell at a 11.7% rate while state and local government declined at a 3.3% pace).

The inflation rate, measured by the GDP deflator, was 1.9%. Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation was 3.8%, but excluding food and energy - i.e., "core PCE" - was 1.5%. If one believes that the core measure is the right one to guide monetary policy, then inflation is still low.

Disposable income was up sharply due to the payroll tax cut that took effect in January - 6.9% in nominal terms - but only 2.9% in real terms (I think that's where you see the effect from energy prices).

Meanwhile the Department of Labor says that unemployment claims are rising again...

The next revision of the GDP figures comes out on May 26.

See also: Free Exchange, Ezra Klein, Calculated Risk.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

FOMC TV

Ben Bernanke held his first post-FOMC meeting press conference today:

Reactions: Mark Thoma, Tim Duy, Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, David Beckworth, Calculated Risk, Free Exchange, Catherine Rampell. The conference was liveblogged by the Times' Floyd Norris and by WSJ reporters.

The general tenor of the reactions (particularly the first five in the list above) is disappointment that it sounds highly unlikely that the Fed will undertake further expansionary policy beyond the $600 billion quantitative easing program currently in progress. This is particularly frustrating in light of the Fed's own revised projections, released today:

The "longer run" unemployment number can be taken as the Fed's estimate of the "natural rate," the lowest rate consistent with non-inflationary growth. The Fed is saying that it expects the unemployment rate to be significantly above the natural rate for at least three more years.

I think this statement was particularly telling:

Also, the academic literature places significant emphasis on expectations and credibility, so the "hawkish" talk is likely partly motivated by a desire to keep a lid on inflation expectations. Of course, credibility ultimately depends on actions consistent with the talk.

While some of us academic types were disappointed in what we see as an excessive emphasis on inflation relative over employment (this is not universal: for a contrary view, see Steve Williamson), the markets may have read things differently. Treasury yields rose today, which suggests that the news from the Fed was slightly less hawkish than expected.

Reactions: Mark Thoma, Tim Duy, Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, David Beckworth, Calculated Risk, Free Exchange, Catherine Rampell. The conference was liveblogged by the Times' Floyd Norris and by WSJ reporters.

The general tenor of the reactions (particularly the first five in the list above) is disappointment that it sounds highly unlikely that the Fed will undertake further expansionary policy beyond the $600 billion quantitative easing program currently in progress. This is particularly frustrating in light of the Fed's own revised projections, released today:

The "longer run" unemployment number can be taken as the Fed's estimate of the "natural rate," the lowest rate consistent with non-inflationary growth. The Fed is saying that it expects the unemployment rate to be significantly above the natural rate for at least three more years.

I think this statement was particularly telling:

I think that while it is very, very important for us to try to help the economy create jobs and to support the recovery, I think every central banker understands that keeping inflation low and stable is absolutely essential to a successful economy and we will do what is necessary to ensure that that happens.While Bernanke is always careful to explain policy decisions in terms of the Federal Reserve Act's "dual mandate" of low unemployment and price stability, here he is subtly putting more weight on the inflation part ("absolutely essential"), relative to employment ("very, very important"). I think this is because "every central banker" is deeply afraid of repeating the mistakes of the 1970's, when high inflation became embedded in the economy, and could only be brought back under control with a very painful dis-inflation in the early 1980's. It may be that, in addition to hurting consumer sentiment, by providing a reminder of "stagflation" of the seventies, the recent run-up in oil prices is also casting a large shadow over the psyche of central bankers.

Also, the academic literature places significant emphasis on expectations and credibility, so the "hawkish" talk is likely partly motivated by a desire to keep a lid on inflation expectations. Of course, credibility ultimately depends on actions consistent with the talk.

While some of us academic types were disappointed in what we see as an excessive emphasis on inflation relative over employment (this is not universal: for a contrary view, see Steve Williamson), the markets may have read things differently. Treasury yields rose today, which suggests that the news from the Fed was slightly less hawkish than expected.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

ARRA MMQB

Another round of Monday morning quarterbacking of the Obama administration's initial fiscal policy drive, which led to the $800bn "stimulus" (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act - ARRA) in February 2009...

One criticism, made Paul Krugman and many others, is that it simply wasn't big enough - in retrospect, it looks like a field goal when we really needed a touchdown.

A natural villain is Larry Summers, in this case because he prevented Christina Romer's case for a bigger program from getting to the president (this doesn't look so funny now). New York Magazine's Krugman profile has Summers' response:

What was unclear was the shape the eventual recovery would take. Some of us hoped that the economy would bounce back quickly, as it had from previous severe recessions (e.g., in 1982, unemployment peaked at 10.8%, but the recovery was brisk; real GDP grew 4.5% in 1983 and 7.2% in 1984). However, the 1990-91 and 2001 recessions, which were much milder, had been followed by sluggish "jobless recoveries." Moreover, as Reinhardt and Rogoff showed, the typical historical pattern is that recoveries in the wake of financial crises are very slow.

Therefore, looking back, in my capacity as another "guy in the bleachers," the main flaw I see is that the stimulus should have been state contingent. That is, the aid to states and many other spending provisions, as well as tax cuts, could have been designed to stay in place as long as they were needed. The act could have contained a trigger to phase out after some recovery benchmark had been achieved, e.g., after the unemployment rate has been below 7% for six months, the stimulus steps down by 50%, with the rest coming off after 6.5% or less unemployment is maintained for a period. Some parts of it could have been tied to state, rather than national, conditions. That might have spared us the ugly spectacle of severe cuts in state services, even as unemployment remains at an appallingly high level. Moreover, knowing that the fiscal support would be in place as long as needed might have served to create more confidence in the recovery, leading to a stronger improvement in private activity. (The natural counter-argument is that such an open-ended fiscal commitment would undermine confidence in the government's ability to handle its debt burden, but I don't think it would have been a problem).

I don't recall the idea of a state-contingent stimulus being raised anywhere at the time, and I have no idea whether it would have been politically feasible or not. Arguably, its just an amplification of the "automatic stabilizers" already built in to the system. Hopefully, there is no next time, but when it comes, perhaps we should give this aspect of the design of policy some further thought.

The Economist's Ryan Avent has another question:

One criticism, made Paul Krugman and many others, is that it simply wasn't big enough - in retrospect, it looks like a field goal when we really needed a touchdown.

A natural villain is Larry Summers, in this case because he prevented Christina Romer's case for a bigger program from getting to the president (this doesn't look so funny now). New York Magazine's Krugman profile has Summers' response:

"[T]here is some element of [Krugman] that is like the guy in the bleachers who always demands the fake kick, the triple-reverse, the long bomb, or the big trade."

Summers concedes that a bigger stimulus would have been the optimal policy in 2009. “The Obama administration asked for less than all that it recognized pure macroeconomic analysis would have called for, and it only got 75 cents on the dollar. But political constraints and practical problems with moving spending quickly constrained us. The president’s political advisers felt, and history bears them out on this since the bill only passed by a whisker, that asking for even more would have put rapid passage at risk.”Ezra Klein suggests we should be asking a different question:

[T]he interesting counterfactual is not “what would have happened if the stimulus had been a bit bigger” but “what would have happened if Barack Obama had been inaugurated a couple of months later?” By June, unemployment was over 9 percent, and the full scope of the emergency was a lot clearer. If that had been the context behind the initial stimulus, I think it’s plausible to think it could’ve turned out very differently.His post illustrates one of the problems with discretionary economic policy - the "recognition lag" - that the state of the economy only becomes clear in retrospect, after the data comes in. This is particularly difficult because, by the time sufficient information to identify trends and turning points is available, the economy may have changed directions again. In most cases, that's a good argument against "fine tuning" macro policies. But I think it was plenty clear in February 2009 that there was serious trouble - payroll employment had declined by over 400,000 in each month from September 2008 through January 2009, and the shock of the fall 2008 financial panic was still fresh in the collective consciousness.

What was unclear was the shape the eventual recovery would take. Some of us hoped that the economy would bounce back quickly, as it had from previous severe recessions (e.g., in 1982, unemployment peaked at 10.8%, but the recovery was brisk; real GDP grew 4.5% in 1983 and 7.2% in 1984). However, the 1990-91 and 2001 recessions, which were much milder, had been followed by sluggish "jobless recoveries." Moreover, as Reinhardt and Rogoff showed, the typical historical pattern is that recoveries in the wake of financial crises are very slow.

Therefore, looking back, in my capacity as another "guy in the bleachers," the main flaw I see is that the stimulus should have been state contingent. That is, the aid to states and many other spending provisions, as well as tax cuts, could have been designed to stay in place as long as they were needed. The act could have contained a trigger to phase out after some recovery benchmark had been achieved, e.g., after the unemployment rate has been below 7% for six months, the stimulus steps down by 50%, with the rest coming off after 6.5% or less unemployment is maintained for a period. Some parts of it could have been tied to state, rather than national, conditions. That might have spared us the ugly spectacle of severe cuts in state services, even as unemployment remains at an appallingly high level. Moreover, knowing that the fiscal support would be in place as long as needed might have served to create more confidence in the recovery, leading to a stronger improvement in private activity. (The natural counter-argument is that such an open-ended fiscal commitment would undermine confidence in the government's ability to handle its debt burden, but I don't think it would have been a problem).

I don't recall the idea of a state-contingent stimulus being raised anywhere at the time, and I have no idea whether it would have been politically feasible or not. Arguably, its just an amplification of the "automatic stabilizers" already built in to the system. Hopefully, there is no next time, but when it comes, perhaps we should give this aspect of the design of policy some further thought.

The Economist's Ryan Avent has another question:

[W]hat if Congress had failed to pass a stimulus at all? Would the Fed have acted sooner or more aggressively or both, and how might recovery have gone differently?Which reminds me of the other thing the administration should have done differently (and this one is harder to explain) - they have allowed several seats on the Federal Reserve Board to remain unfilled for long periods. I agree with Avent that "QE2" appears to have worked. A different Board might have done more of it, sooner, and for longer, and that would have been better. On this point, Brad DeLong is yelling from the bleachers.

Monday, April 25, 2011

Change We Can Believe In (1980s Edition)

In introducing the concept of fractional-reserve banking to my students today, I said that a bank which held reserves equal to its deposits wouldn't be profitable. I'd forgotten this classic example of another way banks could make money:

That was even funnier back in the late 1980s when TV viewers were inundated with the annoying Citibank ads being parodied. Also see this follow-up.

That was even funnier back in the late 1980s when TV viewers were inundated with the annoying Citibank ads being parodied. Also see this follow-up.

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Two Notes on the Continuing Resolution

From the appropriations committee summary of the continuing resolution (i.e, the budget deal):

And:

Petty and shortsighted.

The legislation also eliminates four Administration “Czars,” including the “Health Care Czar,” the “Climate Change Czar,” the “Car Czar,” and the “Urban Affairs Czar.”Anastasia screamed in vain.

And:

For the Department of Transportation, the bill eliminates new funding for High Speed Rail and rescinds $400 million in previous year funds, for a total reduction of $2.9 billion from fiscal year 2010 levels.I didn't realize it was possible to throw trains under the bus.

Petty and shortsighted.

Saturday, April 9, 2011

Macroeconomic Impact of the Budget Deal: Very Quick Estimate

In the e-mail age, there aren't as many envelopes lying around to do calculations on the back of, but I've nonetheless managed to do some rough figurin':

Last night's deal on the budget cuts $37.8 billion in spending. I haven't seen the exact composition yet, but most of it is presumably "domestic discretionary spending" - i.e., the stuff that counts as government purchases in the national income accounts.

Generally we do our macroeconomic calculations at 'annual rates', and since there is about six months left in the fiscal year covered by the budget (i.e., the government budgets start in October), the cut is $75.6 billion at an annual rate. The most recent GDP estimate is an annual rate of $14,871 billion for the fourth quarter of 2010, so lets call it $15,350 billion for the second third quarters of 2011 (based on roughly 5% nominal GDP growth, consistent with FOMC members' forecasts); that implies the cuts are 0.5% of GDP at an annual rate.

If we put the multiplier at 1.75, which is the midpoint of the CBO's range of estimates, the cuts reduce GDP by 0.875% at an annual rate. The rule of thumb known as Okun's law says that, for every percentage point less of GDP growth, the unemployment rate increases half a percentage point. So, over the course of a year, that would put unemployment at 0.4375 higher. Since this is over six months, we're talking about an 0.22 point increase in the unemployment rate. On a labor force of 153.4 million, that translates to a loss of 337,500 jobs.

Like Ezra Klein says, 2011 is not 1995:

A more conservative multiplier estimate of 1 implies a job loss of about 191,750.

The macroeconomic argument for a positive effect from such a deal would rely on the idea that deficit reduction improves confidence in the future. In particular, if the government's future borrowing needs are reduced, there would be less "crowding out" of investment, and if future taxes are reduced, then lifetime disposable income has increased, which would generate higher consumption today. I don't think either of those are relevant to a short-term budget deal when there is significant slack in the economy. However, since many Americans seem to erroneously believe that government spending is hurting the economy, perhaps they will also think this is good for it. Confidence, even for the wrong reasons, matters...

Not much has been said about the composition of the cuts, but I suspect they will be uglier than people realize. While $38 billion sounds small relative to some of the numbers that get thrown around in budget discussions, it is quite significant relative to "nondefense discretionary spending" - i.e., what people usually think of as "the federal government" (see this previous post).

Update (4/14): Maybe not so bad. It appears that the actual cuts are significantly smaller - apparently a significant portion of the $38.5 billion in "budget authority" being cut is money that probably wouldn't have been spent this year anyway.

Last night's deal on the budget cuts $37.8 billion in spending. I haven't seen the exact composition yet, but most of it is presumably "domestic discretionary spending" - i.e., the stuff that counts as government purchases in the national income accounts.

Generally we do our macroeconomic calculations at 'annual rates', and since there is about six months left in the fiscal year covered by the budget (i.e., the government budgets start in October), the cut is $75.6 billion at an annual rate. The most recent GDP estimate is an annual rate of $14,871 billion for the fourth quarter of 2010, so lets call it $15,350 billion for the second third quarters of 2011 (based on roughly 5% nominal GDP growth, consistent with FOMC members' forecasts); that implies the cuts are 0.5% of GDP at an annual rate.

If we put the multiplier at 1.75, which is the midpoint of the CBO's range of estimates, the cuts reduce GDP by 0.875% at an annual rate. The rule of thumb known as Okun's law says that, for every percentage point less of GDP growth, the unemployment rate increases half a percentage point. So, over the course of a year, that would put unemployment at 0.4375 higher. Since this is over six months, we're talking about an 0.22 point increase in the unemployment rate. On a labor force of 153.4 million, that translates to a loss of 337,500 jobs.

Like Ezra Klein says, 2011 is not 1995:

Right now, the economy is weak. Giving into austerity will weaken it further, or at least delay recovery for longer. And if Obama does not get a recovery, then he will not be a successful president, no matter how hard he works to claim Boehner’s successes as his own. Clinton’s speeches were persuasive because the labor market did a lot of his talking for him. But when unemployment is stuck at eight percent, there’s no such thing as a great communicator.Notes:

A more conservative multiplier estimate of 1 implies a job loss of about 191,750.

The macroeconomic argument for a positive effect from such a deal would rely on the idea that deficit reduction improves confidence in the future. In particular, if the government's future borrowing needs are reduced, there would be less "crowding out" of investment, and if future taxes are reduced, then lifetime disposable income has increased, which would generate higher consumption today. I don't think either of those are relevant to a short-term budget deal when there is significant slack in the economy. However, since many Americans seem to erroneously believe that government spending is hurting the economy, perhaps they will also think this is good for it. Confidence, even for the wrong reasons, matters...

Not much has been said about the composition of the cuts, but I suspect they will be uglier than people realize. While $38 billion sounds small relative to some of the numbers that get thrown around in budget discussions, it is quite significant relative to "nondefense discretionary spending" - i.e., what people usually think of as "the federal government" (see this previous post).

Update (4/14): Maybe not so bad. It appears that the actual cuts are significantly smaller - apparently a significant portion of the $38.5 billion in "budget authority" being cut is money that probably wouldn't have been spent this year anyway.

The ECB Tightens

The European Central Bank just announced an increase its policy interest rate from 1% to 1.25%. Their decision highlights some current monetary policy dilemmas.

Core versus overall measures of inflation. As ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet explained:

Inflation targeting and "credibility." A temporary energy-price driven inflation spike may be harder for an inflation-targeting central bank like ECB to brush off. The goal of inflation targeting is to make monetary policy credible - i.e., to keep inflation expectations anchored - but it only works if the announced target is met. Gavyn Davies writes:

The lightest yellow shade are countries with unemployment rates below 7% and the darkest red have rates above 13%, including 14.9% in Ireland and 20.5% in Spain. (A small irony: Eurostat's nifty map tool makes it very easy to illustrate the fundamental flaw of the euro project). In the high unemployment countries, it is hard to imagine that workers would be in a strong position to demand higher wages to make up for the increase in energy prices. But Trichet's worry may make more sense in the parts of Europe where labor markets are tighter. And Trichet can only make one monetary policy. As Floyd Norris puts it:

Core versus overall measures of inflation. As ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet explained:

Euro area annual HICP inflation was 2.6% in March 2011, according to Eurostat’s flash estimate, after 2.4 % in February. The increase in inflation rates in early 2011 largely reflects higher commodity prices. Pressure stemming from the sharp increases in energy and food prices is also discernible in the earlier stages of the production process. It is of paramount importance that the rise in HICP inflation does not lead to second-round effects in price and wage-setting behaviour and thereby give rise to broad-based inflationary pressures over the medium term. Inflation expectations must remain firmly anchored in line with the Governing Council’s aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.That is, the recent blip in inflation is largely due to energy prices, but the worry is that this will lead to higher wage demands and ultimately more general price increases. This would be particularly bad if people began to make plans based on expectations of higher inflation (i.e., expectations became un-"anchored"). Those worries are ill-founded, says Paul Krugman:

Overall eurozone numbers look very much like US numbers: a blip in headline inflation due to commodity prices, but low core inflation, and no sign of a wage-price spiral. So the same arguments for continuing easy money at the Fed apply to the ECB. And the ECB is not making sense: it’s raising rates even as its official acknowledge that the rise in headline inflation is likely to be temporary.Former Fed governor Larry Meyer had a nice op-ed on the subject in the Times last month.

Inflation targeting and "credibility." A temporary energy-price driven inflation spike may be harder for an inflation-targeting central bank like ECB to brush off. The goal of inflation targeting is to make monetary policy credible - i.e., to keep inflation expectations anchored - but it only works if the announced target is met. Gavyn Davies writes:

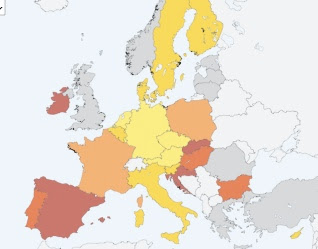

Of course, when an adverse supply shock hits the economy, there are no easy paths for the central bank to adopt, and the ECB will protest that its mandate requires it to hit its CPI inflation target regardless of the consequences for GDP growth. But it can expect no praise if it pushes the economy back into recession.The optimum currency area problem. Or, really, the problem that the euro zone isn't one. The single currency means a single monetary policy. That works if the economies of Europe move together, but they aren't. This map of unemployment rates across Europe illustrates the problem:

The lightest yellow shade are countries with unemployment rates below 7% and the darkest red have rates above 13%, including 14.9% in Ireland and 20.5% in Spain. (A small irony: Eurostat's nifty map tool makes it very easy to illustrate the fundamental flaw of the euro project). In the high unemployment countries, it is hard to imagine that workers would be in a strong position to demand higher wages to make up for the increase in energy prices. But Trichet's worry may make more sense in the parts of Europe where labor markets are tighter. And Trichet can only make one monetary policy. As Floyd Norris puts it:

“If you take the euro area as a whole . . .”This is exacerbated by the fact that several of the smaller eurozone countries are also undergoing sovereign debt crises. David Beckworth has the appropriate musical reference - it may be the final countdown for Europe:

So began a response Thursday from Jean-Claude Trichet, the president of the European Central Bank, as he explained the central bank’s decision to raise interest rates in Europe.

If only there were a “euro area as a whole.”

[T]his move may have begun the countdown to the Eurozone breakup. It is hard to see how else this can turn out. The Germans--the folks who really call the shots in Europe--are reluctant to see the needed debt restructuring in the periphery and are equally reluctant to provide bailouts large enough to fix the problem. So far the Germans have been kicking the can down the road on these issues. With ECB monetary policy now tightening they will soon run out of road to kick the can down.One irony here is that many of the same sorts of people who have taken to criticizing the Fed for "printing money" are also prone fretting that America is sliding down the slippery slope to "European socialism" (trains and universal healthcare - quelle horreur!). Next time Ron Paul says we need to return to "sound money", someone needs to tell him to move to Europe!

Friday, April 1, 2011

March Employment: Sluggish Acceleration Continues

If the US economy was a car, Motor Trend would not be impressed with its acceleration...

The BLS reports that nonfarm payrolls (i.e., "jobs") increased by 216,000 and the unemployment rate decreased to 8.8% in March (from 8.9% in February).

That's the best payroll number since last spring - the economy appeared to be entering a more rapid recovery with 277,000 and 458,000 jobs added in April and May 2010, respectively, before it wobbled last summer. Overall, the March numbers are consistent with an economy climbing out of a deep hole (13.5 million people remain unemployed) at a painfully slow pace.

The slow employment recovery is consistent with the pattern established by the two recessions of the "great moderation" era, in 1990-91 and 2001, but those recessions were quite mild by comparison. This is a disappointment to those of us who were hoping that the a severe recession would be followed by a sharp recovery, like in the last downturn of comparable magnitude, in 1981-82.

The payroll number comes from a survey of firms, and the unemployment rate is calculated from a survey of households. The household survey reported an increase of 291,000 in the number of people employed; the number of unemployed decreased by 131,000 and the labor force increased by 160,000. Labor force participation was steady at 64.2%.

On a non-seasonally adjusted basis, the unemployment rate fell from 9.5% to 9.2%, and payroll employment rose by 925,000. That is, the economy actually added alot of jobs in March, but a large part of that is a normal seasonal increase, so we shouldn't get excited about it.

See also: Calculated Risk, Ezra Klein, Sudeep Reddy.

The BLS reports that nonfarm payrolls (i.e., "jobs") increased by 216,000 and the unemployment rate decreased to 8.8% in March (from 8.9% in February).

That's the best payroll number since last spring - the economy appeared to be entering a more rapid recovery with 277,000 and 458,000 jobs added in April and May 2010, respectively, before it wobbled last summer. Overall, the March numbers are consistent with an economy climbing out of a deep hole (13.5 million people remain unemployed) at a painfully slow pace.

The slow employment recovery is consistent with the pattern established by the two recessions of the "great moderation" era, in 1990-91 and 2001, but those recessions were quite mild by comparison. This is a disappointment to those of us who were hoping that the a severe recession would be followed by a sharp recovery, like in the last downturn of comparable magnitude, in 1981-82.

The payroll number comes from a survey of firms, and the unemployment rate is calculated from a survey of households. The household survey reported an increase of 291,000 in the number of people employed; the number of unemployed decreased by 131,000 and the labor force increased by 160,000. Labor force participation was steady at 64.2%.

On a non-seasonally adjusted basis, the unemployment rate fell from 9.5% to 9.2%, and payroll employment rose by 925,000. That is, the economy actually added alot of jobs in March, but a large part of that is a normal seasonal increase, so we shouldn't get excited about it.

See also: Calculated Risk, Ezra Klein, Sudeep Reddy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)